Harvard & MIT: Morris Chang's Memoir Ch 2 (Part 2)

An English Translation of Morris Chang's Autobiography Vol 1 Ch 2 (Part 1) originally published in 1998

Note: This is an unofficial, non-commercial translation of Morris Chang’s memoir, shared for educational and entertainment purposes only. Full disclaimer below.

Harvard students brimmed with talent

The excellence and diversity of Harvard’s students played a key role in my quick adaptation. Had I gone to a typical American college, I suspect most freshmen would have focused their interests narrowly on sports and social life.

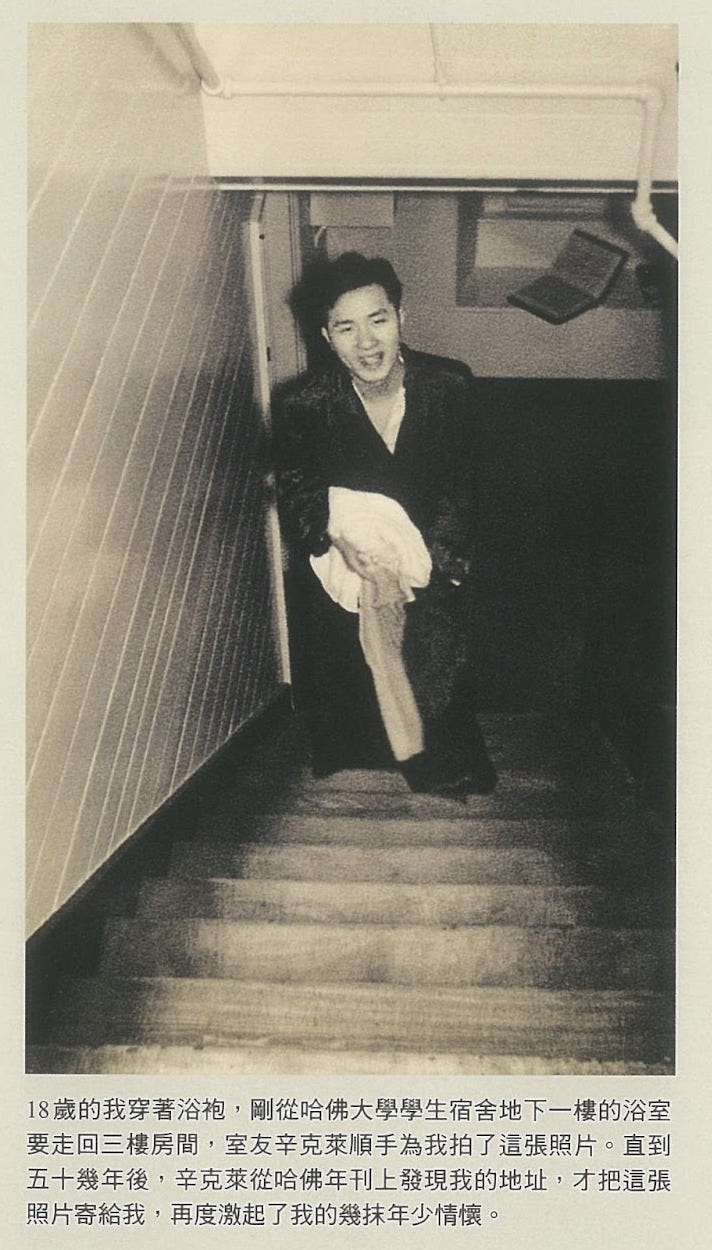

Harvard’s students, however, harbored myriad passions. Among my dorm mates were those with musical training, aspiring musicians who joined me at symphony concerts and operas; others studying architecture or art who accompanied me to Boston’s museums; political science majors who discussed the future direction of Communist China with me; gifted physics students who helped me solve difficult math and physics problems; my roommate Sinclair who introduced me to basketball and ice hockey, and explained the customs of dating; and my close friend Berman, who shared my broad range of interests and served as my literary guide. I was truly fortunate to encounter such an environment in my very first year in America. Later at MIT, I found the students quite different: more diligent yet more reserved, rarely exuding an aura of dazzling talent. They tended toward narrower interests. Compared to Harvard, MIT felt rather dull.

My Harvard year was exhilarating and stimulating, yet also well-disciplined. Except for one weekend trip by train to visit a friend in upstate New York, I stayed on campus, passing time in the dorms and eating in the dining halls. The meal plan provided food six days a week, leaving us on our own for Sundays. I recall that a meal cost about two dollars a day, and we ate very well. At the time, no one fretted about cholesterol or fat; eggs, milk, butter, steak were all deemed healthy. We dined in Harvard Yard’s dining halls, collecting our trays of food and then sitting at long tables for relaxed conversation. The dining atmosphere was orderly; dinner even required a jacket and tie.

My daytime hours were almost entirely consumed by classes and reading. The dorms were quiet during the day, conducive to study. After dinner, the dorms came alive. For serious nighttime study, the library was better. Returning to the dorm usually meant various conversations and discussions on every topic imaginable. Most extracurricular activities also took place in the evenings.

I purchased a season ticket to the Boston Symphony Orchestra, attending a world-class performance once a week. Boston is a cultural capital, frequently hosting renowned musicians. In that year, I heard many live performances. Pianists Arthur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz, violinist Jascha Heifetz, tenor Nelson Eddy—artists whose records I had listened to in Shanghai—now performing before my eyes.

Beyond music, I also savored ballet and theater. One play that gripped me profoundly was Death of a Salesman; for days afterward, I could not shake the tragic fate of its protagonist nor the societal forces that shaped it. Another was Shaw’s Man and Superman. The performance I attended had no sets, merely four famous actors in formal attire reading their lines, yet the hall, seating thousands, was packed. I had read the script beforehand to fully appreciate the performers’ artistry and dramatic atmosphere. The actors delivered lines with crystal clarity—sometimes thunderous, sometimes in hushed, urgent whispers. Their individual skill and synergy were outstanding, leaving an indelible impression.

An enriching intellectual and spiritual life

Opportunities to attend lectures and debates abounded. The recent Communist takeover of the Chinese mainland made “the China question” a hot topic for lectures and debates. Guest speakers included professors, visiting scholars, and politicians. U.S. congressmen considered it an honor to be invited by Harvard student organizations to give speeches, and often obliged. Debates, usually moderated by political science faculty, featured student debaters. Though some student arguments were callow, the overall standard was high.

With such an abundance of intellectual and cultural stimulation, I scarcely had time to worry about sports. Yet Harvard mandated that all freshmen master at least one athletic skill and pass a swim test by year’s end. Those who did not know how to swim chose swimming as their required sport. I was among them. Every Saturday, I reported to the pool for an hour’s lesson. Many classmates quickly learned and passed the test, moving on to more favored sports. But I, ever clumsy in sports, struggled mightily with swimming. Each week, the class dwindled, the coach grew more impatient. When I finally swam 100 meters and passed, the coach was relieved and congratulated me. After I passed, only one other classmate remained. Taking one last look at the pool, I saw him still flailing in the water, struggling valiantly.

In a year of exhilarating and busy exploration, time flew by. At the end of the academic year, my grades were: A in physics, math, and English; B in chemistry and humanities. Harvard graded on a strict curve: roughly 10% A, 25% B, 50% C, the rest D or E. My three A’s and two B’s placed me in the top 10% of the class.

Hemingway described Paris as a “moveable feast.” I apply the same phrase to my year at Harvard. Whether at MIT, in industry, at Stanford pursuing my doctorate, or later working at Texas Instruments—wherever I went, whatever I did afterward—I carried with me this “feast,” savoring its knowledge, interests, and insights. Even decades later in Taiwan, amid circumstances so changed they felt like another world, this “feast” retained its freshness. I could still conjure that rich, ever-changing, refined atmosphere.

Planning for my future and livelihood

During my year of feasting, the mainland changed hands. In October 1949, Guangzhou and Xiamen fell; in November, Chongqing fell; in December, Chengdu fell. The Nationalist government relocated to Taiwan that December. The People’s Republic of China had been founded on October 1, 1949. Many feared Hong Kong was in imminent danger. As the tides shifted, the sliver of hope I had clung to of returning home began to dim. My father’s prophecy that “engineering alone offers a future” rang ever true.

My uncle knew I had broad interests and had regarded Harvard as a year of exploration. Now that a year had passed, and I had not developed any stronger interest in engineering, it was time to consider my livelihood. For young Americans inclined toward engineering, MIT was their top choice. Thus, in Harvard’s second semester, I applied to transfer into MIT’s sophomore class. As for what branch of engineering? To be honest, I hardly knew what each field entailed. I vaguely assumed engineering meant machines—then surely mechanical engineering covered the broadest range. My uncle, though more knowledgeable, was a “liberal” in educational matters, believing young people should choose their own paths. When I asked if mechanical engineering was a good choice, he simply said, “Excellent.” So I applied to mechanical engineering and was accepted.

Before leaving Harvard, I enjoyed one last memorable summer. I enrolled in Harvard’s summer school for a Russian language class and audited “European History After 1815”. The summer atmosphere was more relaxed than the regular term; classmates came from other institutions, and workloads were lighter, allowing more time for extracurricular amusements.

That summer, several Chinese students arrived at Harvard. I had gone a full year with hardly any Chinese friends, or even glimpsing many Chinese faces. Now meeting Chinese classmates felt especially heartwarming. Among them was Gregory C. Chow (Zou Zhizhuang), who had completed three years of economics at Cornell. Within weeks, we became good friends.

Over that three-month summer, we met almost daily, discussing ancient and modern times, East and West. Sometimes we arranged double dates with female classmates. Boston summers are mild, especially at dusk, and strolling under the palm trees of Harvard Yard or along the Charles River was delightful. With female companions, of course, all the more pleasant. The three months passed all too quickly in a cheerful mood.

My parents also came to the U.S. in the summer of 1950, anxious that Hong Kong might soon be taken by the Communists. This was their first time abroad. Though the country’s woes weighed heavily on their hearts, we were at least reunited as a family. The novelty of America lent them some joy in that first year. They visited friends in New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C., and toured many of the Eastern Seaboard’s landmarks.

Transferring to MIT

In September 1950, I reported to MIT as a sophomore in mechanical engineering.

Founded in 1861, MIT had long been recognized as America’s preeminent institute of technology. As the 20th century advanced, national strength came to be measured by technological prowess, and MIT’s prestige soared. During WWII, MIT’s faculty and researchers contributed greatly to American military technology. Its Presidents often served as official or unofficial scientific advisors to U.S. Presidents. The postwar decades were the zenith of MIT’s influence. Its breadth and depth in science and technology were unparalleled.

Today, MIT remains outstanding, but after several decades, numerous competitors have emerged, so it no longer commands the same unrivaled dominance.

When I arrived as a sophomore, MIT enrolled about seven or eight thousand students, half undergraduates and half graduate students, with foreign students making up about 10%. Nominally coeducational, MIT then had only a few dozen female students (about 1%). Currently, the total numbers and the graduate ratio are similar, but foreign students now exceed 30%, and women comprise about 31%—a stark contrast to back then.

At MIT, I resolved to work diligently in engineering. At Harvard, I had absorbed Western culture like a sponge, developed a taste for its literature, arts, and thought, made numerous American friends, and felt integrated into American society. I made tremendous gains.

But in engineering, I had made no comparable progress. Now, as a sophomore in mechanical engineering, and preparing to make a living in engineering, the time had come to apply myself seriously.

Diligence in my chosen field

MIT students bore heavier course loads than their Harvard counterparts. Harvard’s average was four courses per semester; MIT required five or six. The school estimated that each subject required three hours of class and six hours of study per week—around fifty hours total. Many classmates studied even more than fifty hours weekly.

Generally, MIT students worked harder than Harvard students and focused more intently on their specializations. Initially, I found conversations with classmates dull, but soon realized they were not only bright but lived and breathed engineering, even in daily routines. This atmosphere greatly reinforced my resolve. I bonded with several industrious classmates, and we encouraged each other, discussing and questioning together. It was at nineteen, entering MIT, that I truly began serious study in engineering.

As a sophomore, I took six courses, two of which were general education requirements—history and economics. Unlike at Harvard, where I spent most of my energy outside of science, here I channeled most of it into mechanical engineering. In junior and senior years, all my courses were in mechanical engineering.

At that time, MIT’s Mechanical Engineering Department boasted a faculty of masters. In applied mechanics, we had Jacob Pieter Den Hartog; in fluid mechanics, Ascher H. Shapiro; in thermodynamics, Joseph H. Keenan and Joseph Kaye; in materials science, Egon Orowan and Milton C. Shaw. A few months ago, a vice-chancellor from UC Berkeley visited me. Younger than me by some years, also from a mechanical background (though not MIT), he recalled those names with envy, calling the 1950s the golden era of MIT’s mechanical engineering faculty. He agreed that no institution could rival MIT’s academic caliber in that era.

Back then, I did not fully appreciate this “golden age,” but I was impressed by these great masters. In their eyes, the undergraduate and even master’s curriculum was quite fundamental, yet they possessed that rare ability to “penetrate deeply yet explain simply,” making the material easily understood. Such an ability seems possible only for those who fully grasp their subject. I later confirmed this many times in various domains. Another trait was their approach to student questions. American students love to ask questions—some trivial, some profound. These distinguished professors never belittled any query. Simple questions they answered swiftly; for more difficult ones, they would pause, think aloud, and sketch reasoning steps on the blackboard. After a few minutes, they would resolve what we considered a knotty problem. If they could not solve it immediately, they would say: “Let me think it over and tell you next class.” And they never failed to return with an answer. True masters indeed—never stumped, using difficult questions as opportunities to model their thinking process. Clever students learned from this both intellectually and by example.

Feeling the financial pressure

After sophomore year, I began to feel greater financial pressure. Before I left for America, my mother warned that my father could cover only my first year’s expenses. After that, I needed scholarships, part-time work, or both. At MIT, I did have a scholarship, but like Harvard, MIT was a private institution with high tuition and living costs. I had to find work to supplement my income.

I had learned to type as a child. During the half-year when Hong Kong fell to the Japanese and I could not attend school, my father had me practice typing, saying, “at least learn some skills to make a living.” Unexpectedly, it now came in handy. Though I could not live off of it, I could defray some expenses. Before word processors existed, typing jobs were plentiful. Just post a note on the school bulletin board, and clients would come. But typing was more laborious then. To make duplicates, you had to use carbon paper; correcting errors was tedious. The rate was about 25 cents per page (including two carbon copies), taking 20 to 30 minutes per page. So two hours of typing equaled the cost of a meal.

Besides income from scholarships and typing, from my junior year onward, I performed calculation work for professors. At that time, Professors Keenan and Kaye were preparing a revised version of “Thermodynamic Tables”—a hundred-plus pages of densely packed numbers, all of which had to be computed. I spent hours daily at a mechanical calculator. The pay was 90 cents an hour, slightly better than typing. Initially, I thought this technical work might aid my studies, but soon found it monotonous and repetitive. Disappointed, I dared not complain to my “superior,” Professor Kaye, so I turned to a Chinese professor I had met a few times at my uncle’s home, hoping for sympathy or encouragement.

Instead, he sneered and said: “In academia, there are two kinds of work: the kind that requires thought, and the kind that is tedious, repetitive drudgery. Since you have no qualifications for the first kind, you must do the second.” I received no comfort, but I learned a valuable lesson: society is cold, and I must rely on myself. Perhaps this lesson was more useful than any consolation I had hoped for.

After half a year, the thermodynamic tables were complete. Professor Kaye was pleased and assigned me to assist one of his doctoral students with experiments. My wage rose from 90 to 95 cents per hour. Six months later, I was a senior and managed to secure a “Research Assistant” position, an official title with my name listed among university staff, starting at $1.10 per hour. By the time I left MIT, I was making $1.25 an hour—nearly enough to buy a plate of “shrimp and scrambled eggs” in a decent Chinatown restaurant with just one hour’s wage.

The financial pressure made me live frugally. At Harvard, I had dorm housing and meal plans. At MIT, to save money, I rented a cheap room on Massachusetts Avenue, not far from campus. For a few months, I even tried cooking with a group of Chinese students, each taking turns preparing meals. Less than half a year later, I regretted not staying in a dorm. I missed the camaraderie, discussions, and friendships formed in the dorm environment. Living off-campus made my life less disciplined, and I disliked the dirtiness of the cheap apartment and the uncertainty of self-cooked meals. Within a year, I decided to move back to a dorm. Until I married, I always lived in dormitories.

Giving up on changing majors

Economic pressure also compelled me to graduate as soon as possible. Although I had moved through several cities and changed several schools in China, I always kept pace with my classmates. I graduated from high school at seventeen. I had a gap year before going to the U.S., so I was eighteen as a freshman but while at MIT, I knew I wanted to finish by twenty-one.

Therefore, I took the maximum permitted course load every semester, enrolled in summer school, and took the maximum credits allowed. In doing so, I compressed three years (sophomore to senior) of coursework into two academic years plus one summer. In retrospect, this was a major blunder.

When you overload during the regular semester, you inevitably “swallow whole” certain subjects without truly digesting them. The problem was even more severe in summer school because the summer term was shorter than the regular term. Once you fell behind, it was hard to catch up. In regular semesters, lectures were on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with a whole day in between to do homework. If you fell behind, the backlog would not exceed two or three lessons in a week, and you could catch up over the weekend. In summer school, classes met daily and homework was due daily; fall behind once, and the next lecture might not make sense. Fall behind a week, and even the weekend might not suffice to catch up.

Learning needs balance and periods of respite. After my stimulating year at Harvard, I enjoyed a leisurely summer break. At MIT, determined to graduate early, I chose courses that left me breathless all year round, compromising both my learning and quality of life. This was indeed a “major blunder.” I spent five years at MIT versus only one at Harvard, yet I feel far less affection for MIT. My poor choices were a significant factor.

Admittedly, MIT gave me the credentials to find a job. Gradually, I progressed from a state of “unfamiliarity” and “ignorance” of mechanical engineering to “studying it for my future livelihood” and even finding some problems interesting. But that was the limit. I never developed the fervor essential for true expertise—the kind of passion I had once felt for Chinese literature in middle school, or for Western literature at Harvard, or that I would later feel for semiconductors. Still, I maintained decent grades. As a sophomore at MIT, I was again in the top 10% as at Harvard. Later, due to my rushing, my performance slipped. At graduation, my bachelor’s rank fell to the top third; in my master’s studies, I improved somewhat, finishing in the top quarter.

In my senior year, I considered switching to physics or electrical engineering, since I preferred physics and math to other subjects I’d encountered. Of course, these two subjects were core requirements for a physics major, and featured more prominently in electrical engineering than mechanical engineering. But changing departments would have delayed graduation by a year or two. Under the imperative of early graduation, I dismissed this idea.

Disclaimer:

This is an unofficial translation of the memoir of Morris Chang. It is a non-commercial, unaffiliated work intended solely for educational and entertainment purposes.

All rights to the original text and its contents are fully retained by the original author and copyright holders. This translation has not been authorized, approved, or endorsed by Morris Chang, his representatives, or any affiliated publishers.

This content should not be relied upon for scholarly or commercial use, and no part of this translation may be reproduced, redistributed, or sold. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns, please contact me directly.