Morris Chang's Memoir Ch 2 (Part 1)

An English Translation of Morris Chang's Autobiography Vol 1 Ch 2 (Part 1) originally published in 1998

Note: This is an unofficial, non-commercial translation of Morris Chang’s memoir, shared for educational and entertainment purposes only. Full disclaimer below.

For continuity and context, readers are encouraged to refer to the previous installments of this series:

Ch 2: Harvard and MIT

In 1949, the United States stood at the pinnacle of global prestige and authority. Barely four years had passed since the end of the Second World War, and it emerged as the paramount victor, its homeland untouched by devastation. In terms of military power, the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force had displayed their might on every theater of the war, and it remained the world’s sole possessor of the atomic bomb. Economically, despite comprising 5% of the world’s population, the United States generated 40% of global GDP.1 No other nation could rival the American standard of living: a few months’ wages could buy an automobile, two or three years’ savings could purchase a home. Nearly every household owned a refrigerator and washing machine, and many were acquiring that rising novelty—the television set. Since most married women did not work outside the home, the typical family relied on a single breadwinner’s salary; yet even that single salary was sufficient to ensure a comfortable material existence.

“As long as you work hard, you can succeed”

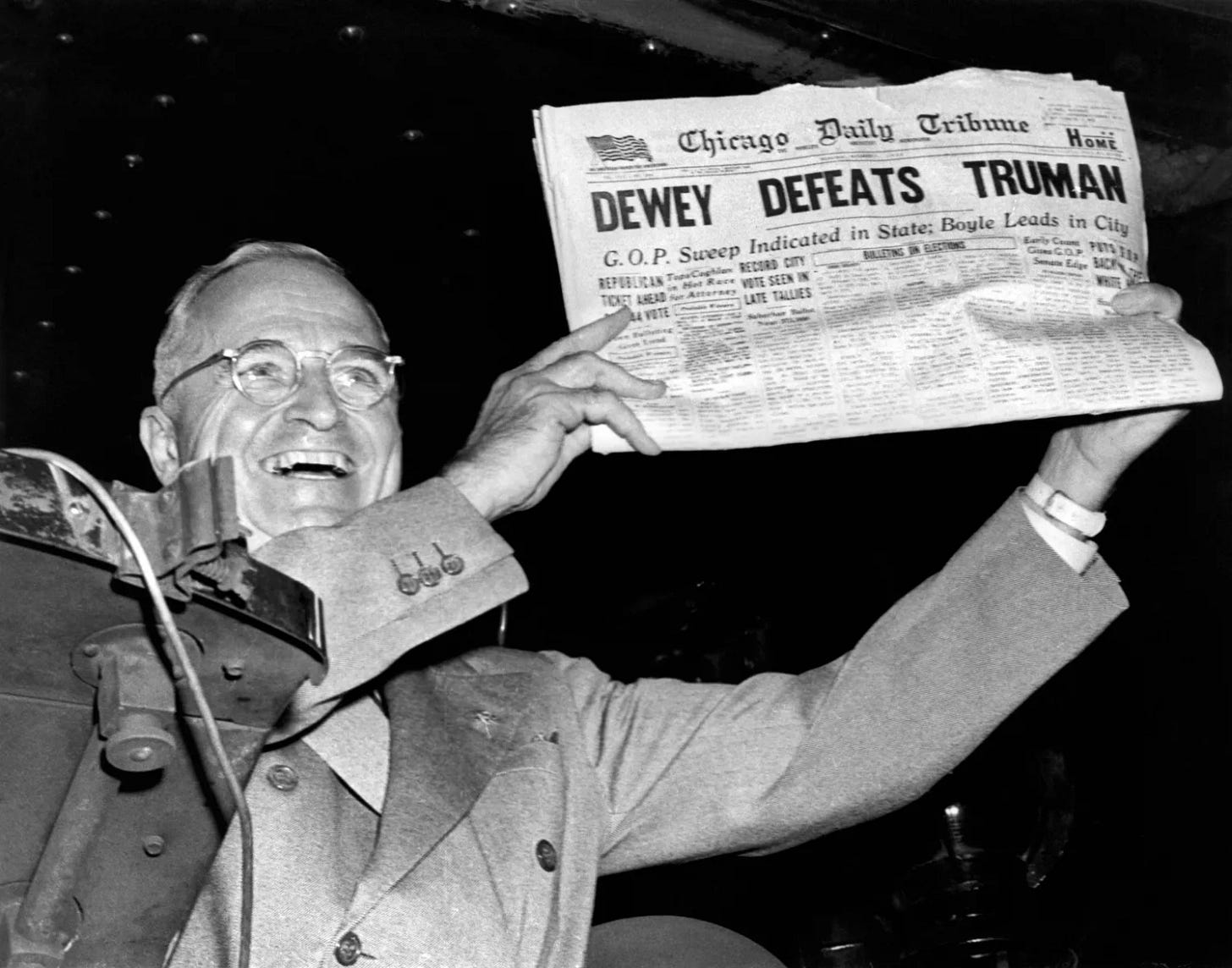

But it was not America’s military prowess nor her boundless economic might that most captivated the peoples of other lands—including me. Rather, it was the democracy and freedoms she upheld, as well as the pervasive ideal throughout American society that “As long as you work hard, you can succeed.” When I arrived in America, it had been eight months since Truman’s unexpected victory over Dewey in the 1948 Presidential election—a surprising triumph people still discussed with relish.

Public opinion then regarded Truman’s win as a victory of the people and of democracy itself. Although Dewey was talented, he struck many as cold and arrogant. Truman, on the other hand, emanated the honest forthrightness of the “common man.” During the campaign, Dewey, confident in his own inevitability, avoided serious debate on national policies. Truman, by contrast, took the offensive, assailing the Republican-controlled Congress with stinging critiques. In response, the people acted: they decided they would rather trust Truman. Although politicians and media pundits, and even nascent polling methods, all forecasted a Dewey victory, the electorate surprised them all by choosing Truman.

At the time, Americans participated in local and national elections at a far higher rate than today, and they were generally more engaged with public affairs. Newspapers and magazines served as the primary sources of information—television would not become a major news medium for another decade or two. Newspapers and magazines covered current events with a detail and depth that television, with its simplified and often entertainment-oriented approach, would later erode. Thus, people’s understanding of national and local politics was often more thorough and nuanced.

Freedom in the United States was not unconditional: the law had to be obeyed, and the law was explicit. Enforcement was diligent, leaving little room for ambiguity.

To someone like me, newly arrived from a chaotic, war-torn land, America’s rule of law in 1949 seemed like another universe. True, the newspapers ran crime stories, but in Cambridge, where I lived, it seemed that most people’s day-to-day lives were untouched by any hint of criminality. The phrase “free to leave doors unbarred at night, your lost items will be left on the road” (i.e., living without fear of theft or harm)—indeed mirrored everyday existence.

As for the cherished ideal “as long as you work hard, you can succeed,” it seemed the shared faith of the general populace. In truth, Americans back then were more industrious than they are today, and every field abounded with examples of individuals who rose from humble beginnings through unflagging effort.

In the 1996 U.S. Presidential election, one candidate was Senator Bob Dole, then in his seventies. He had grown up during the Great Depression (the 1930s), served and was wounded in WWII, and spent his career amid the political upheavals of America’s postwar heyday. While campaigning, Dole remarked that many American values he had grown up with—family, hard work, self-reliance—had eroded. If elected, he pledged to serve as a bridge reconnecting Americans to those lost values. His words struck a chord with many, yet the Democrats mocked his age, saying Dole could only build a “bridge to the past,” whereas they would build a “bridge to the future.” But what kind of future did they mean? More crime? More divorces? More social strife? More social welfare leading to greater dependency on government?

Breathing the air of freedom

In sum, the two or three decades in the mid-twentieth century represented a golden age of American politics, economy, and cultural life. To a world still mired in poverty, chaos, and darkness, America exerted an incomparable allure.

On the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor are inscribed these famous lines:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

What boldness of spirit! What magnanimity! These lines were penned by an American poet, Emma Lazarus, to commemorate the statue’s unveiling in the early twentieth century. Even half a century later, reading these words still inspires a deep kinship in my heart. I did not read this poem until many years after I arrived in America, yet even then I could not help being moved.

Before air travel was common, when European immigrants sailed into New York Harbor on their ocean liners, they crowded the decks, gazing from afar at the approaching Statue of Liberty and moved to tears by the sight. Asian immigrants, arriving by ship in San Francisco, saw no statue, but the Golden Gate Bridge welcomed them to America with equal grandeur. Many immigrants on board were likewise moved to tears upon beholding their first view of America.

Sadly, I traveled by plane and missed that poignant “first glimpse” of America. Departing Hong Kong, I flew via Okinawa to Tokyo, paused about twenty hours, then flew onward via Wake Island and Honolulu, finally landing in San Francisco after roughly forty-eight hours of travel. A relative—an older cousin by about a decade, then a graduate student at UC Berkeley—came to greet me. Upon seeing a youth like me, he found little to discuss, so aside from picking me up, he more or less left me to my own devices. I stayed at a modest hotel in San Francisco’s Chinatown, took the bus to tour the city and nearby sites by day, and ate fried rice at small restaurants in Chinatown by night. A few days later, I boarded a train for Boston, arriving two days later. My uncle’s entire family met me at the station.

Temporarily living with my uncle

My uncle, Professor Sze-Hou Chang, was then thirty-six years old. He had been a top student of the Electrical Engineering Department at Shanghai Jiaotong University, graduating second in his class and had taught at Tsinghua University in Beijing before the war. When hostilities broke out, he followed the university to Chongqing, teaching at Jiaotong University’s wartime campus in Jiulongpo. By the time my parents and I arrived in Chongqing, he had already risen to a full professorship, yet he regretted that he had never studied abroad. After the war’s end, in late 1945, when the chance came to go overseas, he seized it without hesitation, leaving my aunt and their children behind. He traveled alone across the ocean to pursue a doctorate at Harvard. He completed his Ph.D. in less than a year. Thanks to his prior teaching experience in China, he soon secured a faculty position at Northeastern University in Boston. By early 1948, my aunt and my three younger female cousins had also joined him in the United States.

Although a university professor, my uncle’s salary at Northeastern was modest. Well-established professors often supplemented their income by consulting for industry or participating in corporate management, but having just begun his career in America, my uncle had not yet built such networks. As a result, his earnings approximated that of a typical middle-class American. Thus, soon after my arrival, I caught a firsthand glimpse of the American middle-class lifestyle.

My uncle’s family comprised five at that time—three daughters, ages thirteen, ten, and eight, with a fourth child on the way, as my aunt was pregnant. This was not a small family by American standards.

They had a new car, but could not afford to buy a house. They rented a modest apartment in a fairly ordinary neighborhood—one living room, a decently sized kitchen that doubled as a dining area, and two not-very-large bedrooms. One bedroom for my uncle and aunt, and one for the three girls—a bit cramped. Still, they had a washing machine, a gas stove, a refrigerator, a vacuum cleaner, and central heating. At that time, television ownership in the U.S. was about 20%, but my uncle had already bought one, making it the focal point of the family’s leisure time. My aunt managed household expenses prudently, without extravagance, and the meals were delicious and nutritious. The girls attended public schools, so tuition and fees were minimal. Friends frequently dropped by; if they arrived at mealtime, my aunt would simply cook an extra dish or two. On weekends, the family often drove out for outings, watched ball games or movies. In short, they lived a contented and joyful life. Their standard of living was likely above that of a Taiwanese middle-class family today.

Meeting my close friend Berman

I stayed at my uncle’s place for a week, sleeping on the living room sofa—obviously a temporary arrangement. In the second week, I moved into a privately run “rooming house.”

In American cities, it was common for families to rent out one or two spare rooms. Some older couples, with grown children living elsewhere, rented out rooms to supplement their retirement income. Younger homeowners might have stretched themselves financially to buy a bigger house and needed the rental income to cover expenses. Such rooming houses shared a front entrance with the landlord’s family. Generally, no meals were provided, and tenants had to abide by strict rules: no loud radios, no rearranging furniture, no opposite-sex visitors in the room, no visitors at all after 10 p.m. The advantage lay in the low cost: I paid seven dollars a week, significantly cheaper—perhaps one-fifth to one-tenth the price of a decent hotel. A further benefit, if the landlord was friendly, living there could offer a sense of homeliness that a hotel could not provide.

Though I only stayed at my uncle’s home for a week, throughout my college years, I always considered it my “home”. Nearly every weekend I would visit; if I had questions or difficulties, I would consult him first. He remained a professor and researcher at Northeastern for decades, published numerous papers, and educated many students. After retirement, he moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. His children now all reside in the western United States, and he and my aunt, both in their eighties and healthy,2 enjoy a peaceful retired life surrounded by grandchildren.

In late September, Harvard classes began. A few days before the start of term, students could move into the dorms. I moved in on the very first day.

Freshmen at Harvard lived in the Harvard Yard. Several dormitories encircled the Yard, each housing about a hundred students. Though these were century-old buildings, somewhat antiquated, the rooms were spacious. Typically, two students shared one room. One could apply for a single, but singles were limited and cost more. My uncle had advised me to take a double to facilitate meeting friends, so I did not apply for a single. Since I knew no one at Harvard, I simply allowed the college to assign me a roommate—a common situation for many freshmen.

My room was on the third floor. When I moved in, my roommate had not yet arrived, but on the second floor, I encountered another new student also moving in. His name was Berman, from a suburb of Boston. His father taught English at a local high school, and Berman himself planned to follow in those footsteps by studying literature. After we finished hauling our luggage, we went together to a nearby café for sandwiches. We hit it off instantly. That very day, Berman said that since neither of us knew our roommates, and as we had such an affinity, why not request to be roommates ourselves? I politely declined, not wanting to offend a roommate I had yet to meet, and also feeling his invitation was quite sudden. Nonetheless, Berman soon became my closest friend in those college years. That winter vacation, I visited his home—a charming little house. His parents were kind and friendly, his younger brother a polite young man, and their household radiated warmth.

I also took Berman to my uncle’s home to introduce him to my family. Even after I transferred from Harvard to MIT, I frequently met with Berman. When I got married, he served as my best man, and his whole family attended the wedding. We gradually lost touch after graduation, but he remains in my fond memories.

Before entering Harvard, I knew no Americans personally. My understanding of Americans came entirely from books, which portrayed them as enthusiastic and straightforward, but not easy to form deep friendships with. Berman shattered that stereotype right from the start. Over the decades, I made many close American friends, and in recent years many in Taiwan as well. I believe forming and sustaining friendships is universal across countries: treat people sincerely and you will not lack friends.

Dispelling my fear of racial discrimination

My assigned roommate, Sinclair, was the son of a Columbia University professor, hailed from New York, and wanted to study anthropology. Handsome and athletic, soon after term began, he amassed a following of female admirers. Sinclair also became a good friend. He often invited me to ball games or dances, sometimes introducing his female friends to me.

I, in turn, invited him to concerts, lectures, and debates. Whether I attended a game or a dance with him, or whether he came to listen to music or public talks with me, we always had a delightful time.

In the days before and after the start of classes, classmates moved in gradually. Over the ensuing weeks, I befriended nearly a hundred young people of varied cultural backgrounds and interests, though broadly similar in age and academic aspiration. Among these, several became close friends that year. Of those hundred or so, not a single one displayed hostility because I was Asian. True, a few were indifferent, but they were generally indifferent toward everyone. Whatever anxiety I had harbored about “racial discrimination” dissolved quickly after I enrolled.

In 1949, Harvard’s freshman class numbered about 1,100. Its minority composition was as follows: exactly one African-American U.S. citizen, and a total of fourteen foreign students—eight from Central and South America, three from Europe, one from Africa, and two from Asia (myself and one Japanese student). Thus, the class was almost entirely white American. Their interests were wide-ranging: among the residents of my dorm were students pursuing physics, mathematics, chemistry, anthropology, political science, economics, medicine, and diplomacy. I seemed to be the only freshman intent on studying engineering. Whenever it was my turn to state my academic plans and I said “engineering,” nearly everyone asked in unison: “Then why aren’t you at MIT?”

At the start of the term, we selected our courses. The usual load at Harvard was four courses per semester, with a maximum of six. My uncle suggested I take five. Freshmen underwent a general education plan—only three courses could be in one’s proposed major field, and the rest had to lie outside it. Another requirement: foreign students had to take English. American students could test out by passing an English exam; about one-third failed and thus had to take English as well, making it the largest freshman class.

Overcoming the language barrier

Out of my five chosen courses, four were essentially predetermined: three in the sciences—physics, mathematics, and chemistry—plus English. The fifth course? I consulted the foreign student advisor, a kindly middle-aged professor. He glanced at the course catalog and said, focusing on the humanities section, “The Humanities course introduces Western cultural history. It should be very meaningful for you.” Thus, my five first-year courses were set.

Soon I discovered the varying difficulty levels. Nanyang Model High School in Shanghai had trained me well in math and science; even during my year out of school, I had kept up with these subjects, so math and physics posed no great challenge. Chemistry was never my favorite, but I could manage it thanks to my solid preparation.

English was another matter. Although I had studied English since primary school in Hong Kong, and my English level was above the average Chinese high school graduate, I had rarely used English outside the classroom. Arriving in the U.S., my spoken English sufficed only for basic communication. In writing, though I knew grammar rules better than most Americans, I lacked their natural fluency in composing letters or essays. Entering the English course, I felt quite apprehensive.

The outcome, however, surprised me. Our readings were drawn from modern literature (Hemingway in particular—our instructor adored him, and I too became a Hemingway devotee) as well as politically significant texts of literary merit, such as speeches by Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Churchill. Since childhood, I had felt the allure of Chinese literature; now, in my short year at Harvard, I began developing a similar love for English. Within a few months, my initial unease gave way to genuine enjoyment. Not only did I read all assigned texts, but whenever time allowed, I also delved into the respected works of modern English literature, philosophy, politics, and economics. During that single year at Harvard, I read more widely and voraciously than I ever would again. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Galsworthy, Sinclair Lewis, Jane Austen, Shakespeare, Shaw, Churchill’s WWII memoirs, famous speeches by modern American Presidents, U.S. histories, H.G. Wells’s The Outline of History, several English-language works on China, even monumental classics like Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, and Marx’s Das Kapital.

In addition to these great works, I subscribed to two newspapers: The New York Times and The Christian Science Monitor (published in Boston), as well as Time magazine.

Homer, Shakespeare, Shaw

Another factor that lured me headlong into English was the Humanities course chosen so casually by my foreign student advisor. Before classes began, all I knew from the syllabus was that it introduced the evolution of Western culture. On the very first day of class, the professor explained that we would approach cultural history by studying the great classics that shaped their eras. He enumerated our texts for the full academic year: starting with Homer’s Iliad (circa 8th century BCE), then the Roman poet Lucretius, then John Milton’s 17th-century English epic Paradise Lost. In the second semester, we would tackle Shakespeare’s plays, then Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and finally plays by George Bernard Shaw. “If time remains, we may read some modern works,” he added lightly. As class ended, he gave a swift directive: “For next class (two days later), read the first five chapters of the Iliad.”

Of course, I immediately bought a copy of the Iliad and set to work. But, oh my! To my then-limited English, reading ancient Greek poetry in translation felt like a foreigner barely versed in colloquial Chinese tackling the The Book of Odes. That afternoon and evening, after many hours and countless dictionary checks, I finished the first chapter of the Iliad. Dishearteningly, most of my classmates were literature-focused, many already acquainted with the Iliad. Berman, who was in this class, had read it in its entirety! Competing against them, I was at a pronounced disadvantage. Over the next few months, although Humanities was just one of my five courses, I invested as much time and effort into it as I did on two other courses combined.

This arduous effort continued for months. Gradually, ancient English prose no longer seemed so baffling, and I even began to find pleasure in it. By second semester, reading Shakespeare’s plays had become a delight, and Shaw’s plays even more enchanting. Even the once-dreaded Iliad, when reread, revealed a wealth of captivating Greek myths, some of which remain vivid in my mind. Recently, during a business negotiation with an American, I quoted the prophetess Cassandra from Greek mythology. Afterwards, he asked how I knew such myths. I replied that I had read Homer decades ago. He was astonished: “Today Americans rarely read Homer; how unexpected that a Chinese man should outpace us!”

English as my primary language of thought

In that single year at Harvard, my progress in math, physics, and chemistry could be called steady, but in English I had a breakthrough. The English course familiarized me with modern authors, while the Humanities course guided me into the venerable classics. Outside of class, I read numerous newspapers, magazines, and seminal works. English class demanded a short essay every week and a long essay each semester; Humanities required frequent reports and papers. In conversation, except on weekends at my uncle’s house, I spoke English exclusively. In that year, all my visual, auditory, spoken, and written expressions were wholly in English. Gradually, English displaced Chinese as the language of my thoughts.

This taught me the value of age and environment in language acquisition. At six, I moved to Hong Kong, learning Cantonese as fluently as a local child. At twelve, I moved to Chongqing and effortlessly picked up Mandarin. By eighteen, learning a new language was harder—one needed a special environment and concerted efforts. Harvard provided precisely that environment, which in turn spurred my determination. After a year at Harvard, English had become my primary language; I thought in English and expressed myself best in English.

Not until much later, when I moved to Taiwan, did I need to revert my primary language back to Chinese. By then, I was well into middle age, and making this linguistic reorientation proved difficult. Although my childhood foundation remained, it took several years of effort before I once again began to think in Chinese and express myself naturally in it. Mastery of any language requires sustained practice. Even writing this autobiography in Chinese today is partly an exercise to keep honing my command of Chinese.

Beyond language, Harvard erased the distance I had felt between myself and Americans. For that one year, I had only American friends. I had arrived a timid foreign youth, regarding Americans as strangers and fearing social missteps or discrimination. After a year, I mingled naturally, unburdened by notions of race or nationality.

Disclaimer:

This is an unofficial translation of the memoir of Morris Chang. It is a non-commercial, unaffiliated work intended solely for educational and entertainment purposes.

All rights to the original text and its contents are fully retained by the original author and copyright holders. This translation has not been authorized, approved, or endorsed by Morris Chang, his representatives, or any affiliated publishers.

This content should not be relied upon for scholarly or commercial use, and no part of this translation may be reproduced, redistributed, or sold. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns, please contact me directly.

Reflects the 1998 original publication date